This post is part of the Beyond the Cover Blogathon running April 8-10 over at Now Voyaging and Speakeasy. I hope you’ll enjoy this post as well as the many other entries.

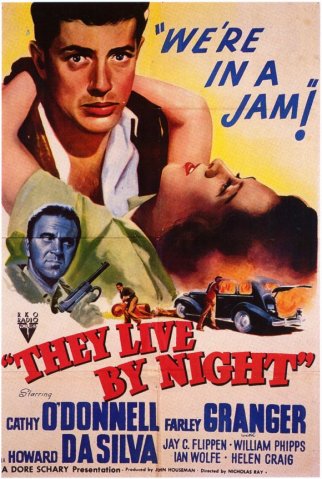

When you think about the time, effort and people involved in bringing a novel to the screen, it’s a wonder adaptations happen as quickly as they do, or even at all. Sometimes the process is relatively short. (Two years is pretty quick, even these days.) In extreme cases, the original creators have departed this world long before their film is ever released. Other productions fall somewhere in the middle. Edward Anderson’s novel Thieves Like Us was published in 1937 during the final years of the Great Depression, but the the story wasn’t filmed until 1947. Even after it was finished, the film sat on a shelf for two years and might have sat there even longer if not for some enthusiastic filmgoers in the UK. But timing is a strange thing, and in some cases it’s everything. Had Nicholas Ray’s They Live By Night remained on the shelf, Alfred Hitchcock would likely never have seen Farley Grainger to cast him in Rope and Strangers on a Train, we probably wouldn’t have Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (at least not in the same style), and the entire canon of film noir would have been without one of its finest, most unique pictures.

Anderson’s depression-era novel Thieves Like Us achingly reflected the time in which it was written. People always do what they have to do, especially in the midst of desperation. The book’s lead characters Bowie, Chicamaw and T-Dub are no exception. Their crime is robbing banks, primarily because that’s where the money is, but also because banks aren’t “real people.” But banks contain bankers, and T-Dub figures that “They’re thieves just like us,” a statement he issues several times in the novel.

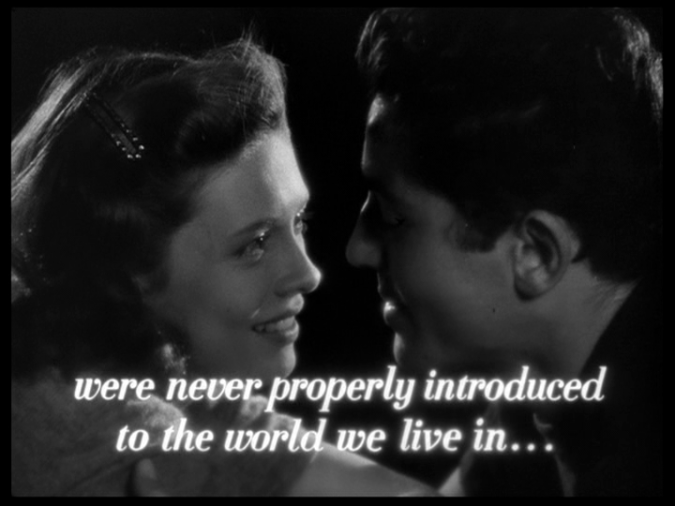

Right from the novel’s first page, Anderson shows us we’re in a crime story: there’s a prison escape, bank robberies, hiding out on the lam, the types of activities we’d expect from a crime novel. In the opening shot of the film version, however, Nicholas Ray shows us a touching scene of Farley Grainger and Cathy O’Donnell in a tender embrace, the screen titles proclaiming “This boy… and this girl… were never properly introduced to the world we live in. To tell their story…”

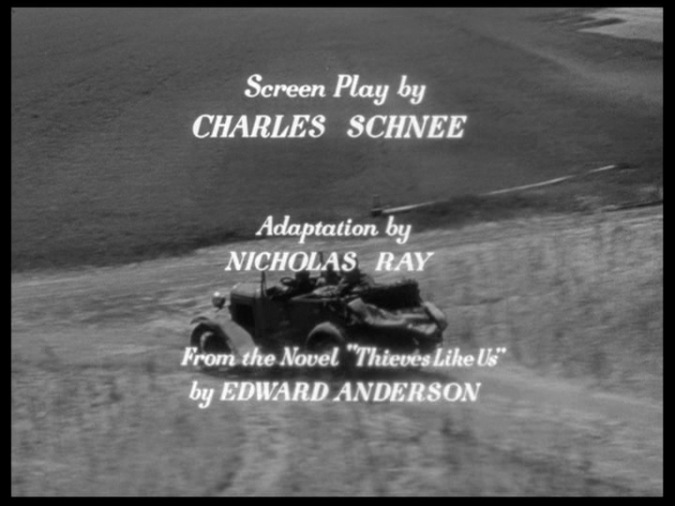

Underneath this prologue we hear the lush sounds of the song “I Know Where I’m Going,” an ironic and yet significant choice. The prologue is clearly meant to tell audiences that this is not going to be primarily a crime picture, although the story moves quickly to three guys committing crimes. This is a bit of a jarring transition, but almost immediately we see these men speeding down a rural road in a stolen car, but we see it from above. Ray filmed this sequence from a helicopter and if he wasn’t the first to do so in an American film, he was probably the first to have done it so effectively. The shot gives us the impression that this was not shot on the backlot, not in front of a process screen, this was really happening. It also gives us something of a God’s eye view, which carries many implications which creep up at various points in the film.

Bowie (Farley Grainger, left), Chicamaw (Howard Da Silva, driving) and T-Dub (Jay C. Flippen, second from left) have just escaped prison in a hijacked car. In the book we know only from a newspaper article that Chicamaw and T-Dub are several years older than Bowie, but in the film the age gap is evident in every frame: Da Silva and Flippen are not only older actors than Grainger, but their faces are made to look more hardened and weathered. (Da Silva also sports a creepy-looking blind right eye, a touch added by Ray that’s absent from the book.) While in Anderson’s novel the three are friends on fairly equal footing, in Ray’s version, Chicamaw and T-Dub are clearly manipulating Bowie, urging first, then later pressuring him to abandon any ties to Chicamaw’s niece Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell) and stick with them, constantly reminding Bowie that it takes a team of three to rob a bank.

While the trio continues to rob banks, their exploits are communicated through newspaper accounts in the book and radio broadcasts in the film. The radio broadcasts are obviously better suited to film, since they constantly interrupt characters’ conversations and also contribute to the “voice of God” omnipresence established visually by the opening helicopter shots. A palpable sense of dread runs through many film noir movies, and we certainly sense it in many scenes here, the most unusual of which occurs as Bowie and Keechie are about to get married.

A word about this marriage. Of course, things move far more quickly in a movie than they do in a novel, and with the film’s opening, we’re not surprised that Bowie and Keechie are headed to the altar in a relatively short amount of time, but in the book there is no wedding; Keechie gets pregnant while not married to Bowie. There was no way that was going to fly with the Production Code firmly in place, so Ray had to add a scene that showed the couple getting married. Yet what could have been a perfunctory scene provides one of the most dread-filled moments in the film as Bowie and Keechie approach the home of a Justice of the Peace (Ian Wolfe, center). Their walk up to the front door is filled with shadows, dread, and a sense of awe. In the Warner Brothers DVD commentary, Eddie Muller mentions that the scene looks like it came from a Val Lewton movie.

Ray’s film is much more focused on the story of Bowie and Keechie than is the novel, which again, seems clear from the film’s opening. Ray has gone to great lengths to make us care about these characters, to show us that in many ways, they’re strangers in a strange land, kids who know very little about life or love. In one scene Keechie tells Bowie “I don’t know much about kissing.” Bowie replies, “I don’t know too much myself.” Such an exchange would seem corny or even laughable in most other films, but Grainger and O’Donnell play their roles with such innocence and wonder that we believe them. Although the chemistry we see between Grainger and O’Donnell is different than what we see from Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in Bonnie and Clyde (a film They Live by Night clearly influenced), it never feels artificial or strained. All of their scenes together are outstanding, but the movie belongs to O’Donnell.

Keechie is the moral landmark of the film. She’s lived with criminals all her life, had them in her family, but now wants something better. She knows little of the real world, and maybe even feels she hasn’t had much of an influence on the men in her family, but she sees the goodness in Bowie despite the crimes he’s committed. O’Donnell’s performance conveys strength and vulnerability, intelligence and innocence, a toughness and a weary yet angelic grace. I have never forgotten her performance in the film’s final moments and I suspect you won’t either. Cathy O’Donnell died far too young (at 46) and is discussed far too infrequently these days. After revisiting They Live by Night, I feel the urgent need to watch every film she ever made. Don’t be surprised if you feel the same way after watching this film.

There’s a wonderful moment after Bowie survives a car wreck and is hiding out with Keechie in her uncle’s cabin. Bowie’s fingerprints have been found on a gun and the cops are looking for him. “You can’t stay here,” Keechie says, but she allows him to stay the night anyway. O’Donnell stands up, turning away from Bowie but toward the camera. A whole range of thought and emotion travels across her face as she braves her way through her next line, “I’ll go with you if you want.”

I’m not exactly sure how Ray achieved these wonderful performances, but clearly he did. In the commentary with Eddie Muller, Farley Grainger calls Ray’s method of directing “alive” and unique. Ray wasn’t a dictator on the set and Grainger has nothing but good things to say about him in the commentary. It’s obvious Ray cared about his characters and wanted us to care as well. I don’t think anyone watching the film then or now cannot be affected by them.

The book was sold to RKO in 1941 by Roland Brown and was then knocked around for several years by several would-be producers, handing it to several writers who each took a crack at the story. Finally John Houseman gave the book to Nicholas Ray, who loved it. Dore Schary, RKO’s Production Chief at the time, pulled some strings and made sure it was Ray and no one else who’d wind up directing the movie. Upon completion of the film, the studio didn’t know what to do with it. When Howard Hughes took over RKO in 1947, he shelved many films, including They Live by Night. As noted above, the film was released first in the UK and later in America, where it recorded a loss of $445,000 (the equivalent of $4.5 million in 2016). Yet if audiences didn’t pay attention, many filmmakers did, such as the aforementioned Alfred Hitchcock, Arthur Penn, and several others.

Anderson’s novel is a fine work, but in Ray’s hands it becomes the framework of a noir classic that seems to strike more of an emotional punch. Of course the medium of delivery is different, and while the novel is still enjoyable in its own right, They Live by Night transcends the novel’s depression-era setting, making it a story audiences find unforgettable in any era.

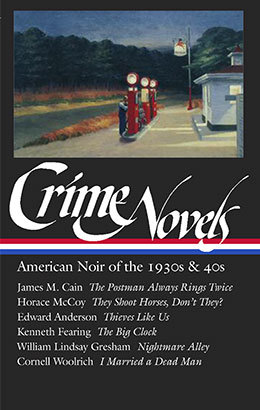

Thieves Like Us is still in print, most recently from Black Curtain Press and also part of a very impressive Library of America collection called Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 40s which also includes The Postman Always Rings Twice, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, The Big Clock, I Married a Dead Man (filmed three times as No Man of Her Own, I Married a Shadow, and Mrs. Winterbone) and Nightmare Alley.

They Live by Night is available as a double feature on a Warner DVD with another Grainger/O’Donnell noir, Side Street, directed by noir veteran Anthony Mann. This double feature is also part of the wonderful Warner box set Film Noir Classic Collection Vol. 4, which also includes Act of Violence, Mystery Street, Crime Wave, Decoy, Illegal, The Big Steal, and Where Danger Lives. This set is hard-to-find and expensive on the secondary market, but if you can find it at a reasonable price, jump on it. What we really need is a nice restoration/Blu-ray treatment for They Live by Night. It’s certainly deserving.

UPDATE 6/17: They Live by Night is now out on Blu-ray as a Criterion release with several nice supplements.

Photos: via Libri, Jonathan Rosenbaum, New Granada, Mubi, Derek Winner, Twenty Four Frames

Pingback: Noirvember is Coming… Here are 30 Suggestions: | Journeys in Darkness and Light

Pingback: 2016: The Year in Review | Journeys in Darkness and Light

Great job and fabulous post as usual! I haven’t seen either of these films but now I am eager to! Thank you so much for joining us!

LikeLike

Pingback: Movies Watched in April 2016 Part I | Journeys in Darkness and Light

Thanks, Kristina! Warner has been restoring and releasing so many film noir movies on Blu-ray recently I’m crossing my fingers that this one will also get an upgrade soon. Thanks again for having me for the blogathon!

LikeLike

Great post, I read this in that same Crime Novels book, borrowed from my library and renewed all summer, it seems like 🙂 ate up those works and wanted to write like that. Agree about O’Donnell, so touching and love this movie. Thanks so much for joining the blogathon!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Patricia – You’re right, the film IS a heartbreaker! Thanks for stopping by.

LikeLike

I can’t speak to the novel, but your review of the film perfectly highlights what an emotional experience it is and your praise of Miss O’Donnell is no less than her due. I would run off and watch “They Live by Night” right now except it is not a night to have my heart broken.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: #BeyondtheCover Day 2 Recap – Now Voyaging